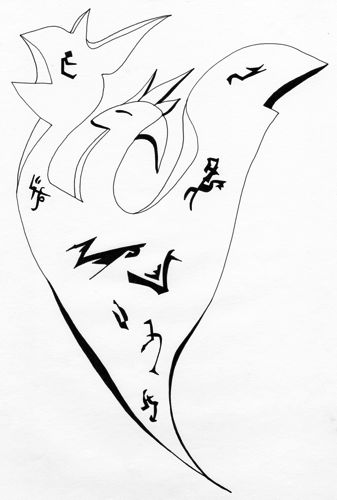

Saroyan Envelope by Jenifer Angel

(This article appeared in the Anderson Valley Advertiser January 2012)

“I claim there ain’t

Another Saint

As great as Valentine.” Ogden Nash

The notices currently taped to both sides of the glass doors of the Mendocino Post Office proclaim that starting February 14, 2012, our post office will henceforth be closed on Saturdays, and postal business shall only be conducted Monday through Friday from 8 AM to 4 PM. That our government, otherwise known as the Council of Evil Morons, would choose Valentine’s Day to kick off this latest contraction of our terrific postal system strikes me as ironic and cruel, as well as evil and moronic.

I and most Americans over fifty first learned how the postal system worked when we were in First and Second Grade and our teachers helped us create and operate our very own in-classroom post offices for the purpose of sending and receiving Valentines to and from our classmates. At Las Lomitas Elementary School we had actual post offices (built by handy parents) that took up big chunks of classroom real estate. These one-room offices featured windows behind which stood postal workers from whom we could buy stamp facsimiles (fresh from the mimeograph machine) to affix with edible white paste to our properly addressed envelopes. These envelopes contained store bought or handmade Valentines, and we would drop these childish love missives into cardboard mailboxes located across the rooms from the post offices. Then every hour or so postal workers would open these mailboxes, empty the contents into transport bags, and carry the mail to the post offices wherein the letters would be sorted into cubbyholes bearing the names of the recipients. And we, the children, got to be the postal workers and do all these fun jobs. How cool is that? For a six-year-old, way cool.

These Valentines postal operations stimulated many other sectors of our classroom ecology. Making art took on new and urgent meaning, as did writing. Anyone could send a regular valentine, but only artists and poets could make valentines covered with glitter (affixed to that same edible paste) bearing heartfelt original (or accidentally plagiarized) rhymes. Roses are red, violets are blue, please be my Valentine, shoo bop doo wah.

Valentines were the gateway drugs that turned me into the snail mail addict I am today, which is why I am so sad and angry about the decline and impending fall of our beloved postal system. Yes, I appreciate a good email missive, one without typos or grammatical errors; but the best email pales next to a mediocre piece of real mail found in my post office box, a one-of-a-kind Easter egg of love waiting to be discovered amidst the bills and junk mail, something made just for me that took someone more than a few seconds to compose and send, something steeped in what psychologists call “quality time”—loving attention undivided.

“Love is metaphysical gravity.” Buckminster Fuller

Get over it, Todd. No. I take Marshall McLuhan’s observation “the medium is the message” as a warning that what we think we’re doing may not be what we’re actually doing. McLuhan was speaking about mass media, television in particular, a medium through which I thought I was watching shows I wanted to watch, when in actuality I was allowing myself to be seduced by processes designed to entrain me to think and feel the way our corporate overlords want everyone to think and feel. Television is a medium of conquest and control. The message of that medium is “Do and be and buy what we tell you to do and be and buy or you will never be safe and happy. Ever.”

So it came to pass that I and many other people figured out the real message of mass media and television and broke free from that enslavement and stayed free long enough to help engender and partake of a brief renaissance of creative freedom known as the Sixties, a cultural revolution largely defined by its independence from mass media and corporate control. Some say the Sixties lasted into the 1970’s, and some say reverberations of that renaissance continued into the 1980’s, but for however long the groovy vibes of the Sixties kept on vibing, the important thing to know is that the innovative energy and expressions of that renaissance were eventually captured and drained of their power by the corporate media apparatus; and the next iteration of television was the computer and the internet and all the attendant satellite devices that define this digital age.

When I quit watching television in 1969, very little else changed in my life. My arts of writing and music were independent of television, and communications for personal and business matters were fast and effective by telephone and through the post office. But a couple years ago when I came out of a trance to find myself watching a basketball game on my computer, having sat down with the specific intention of rewriting a story, it suddenly dawned on me that computers are nothing more than interactive televisions, and now, oops, virtually all my personal and business dealings are inextricably bound to the use of the computer. Today I send my essays to the Anderson Valley Advertiser and other prescient publishers via email, I offer my music and books and art for sale through the internet, and to abstain from using my computer in the same way I abstained from using television would render me immediately and entirely removed from all but the most local of cultures, counter or otherwise.

Yet to stay hooked up to my computer is to be an active and addicted user of a medium that is the message, “Do and be and buy what we tell you to do and be and buy or you will never be safe and happy. Ever.” Except just as there are more layers to the computer/internet interface with our lives than there were with that earlier version of television, so are there more layers to the new medium’s message. Now, along with being told a million times a year what to do and be and buy, we are also compelled through the brutal elimination of alternatives to spend most of our time peering at our computer screens if we wish to feel connected to what we think is most important and meaningful, i.e. what is happening right now in those fields of endeavor we are most interested in.

Post offices, in my view, are among the last few vibrant vestiges of the non-computer way of doing and being, which is the real reason the Council of Evil Morons wants to strangle that marvelous system; so there will be no alternative, none at all, to computers and the internet as a means of doing and being, except on a local basis—very local. Which brings me to my latest idea for kindling the next cultural and social and political renaissance that will save the world and usher in the long awaited age of global enlightenment, which then may or may not precipitate contact with brilliant aliens who have been waiting for us to make the evolutionary leap from stupid selfish poopheads to smart generous sweetie pies.

My idea is that we start our own local post offices, without the aid of computers. We can use telephones to get the ball rolling, but not cell phones. These extremely local post offices will be adult versions of the post offices we had in First and Second Grade, manned by fun loving volunteers. Stamps created by a wide range of local artists will cost a nickel. You will need one stamp for every ounce of mail you send. Post office boxes (cubbyholes) will rent for ten dollars per year. The money collected from selling stamps and renting cubbyholes will go into maintaining the postal buildings with their clean and commodious adjoining public restrooms and teahouses.

Among the many cool things about these local post offices will be that they will be open seven days a week from morning until night, they will have tables and chairs where people can sit and write letters and decorate envelopes and gossip, of course, and they will have multiple gigantic well-maintained bulletin boards whereon anyone may post anything. Neato one-of-a-kind rainproof mailboxes created by local artisans will be scattered throughout the local watershed—and mail will be collected from these neato mailboxes several times a day and transported to the post office in colorful burlap bags. Then the letters will be sorted into our cubbyholes throughout every long day, thus making everyone feel safe and happy.

Yes, it would be easy to set up this kind of local post office using computers, but making something easy doesn’t necessarily make it good.

Todd’s snail mail address is P.O. Box 366 Mendocino CA 95460