(This article appeared in the Anderson Valley Advertiser March 2013)

My uncle David Walton died in China on March 8 at the ripe old age of eighty-seven, just a week ago as I write this, yet I have already received an email with photographs from the lovely memorial service that was held for him in Xichang where David lived and taught English for the last several years, his Xichang friends and students in attendance. And that memorial service email was just one of many I have received so far along with several phone calls from a tiny fraction of the hundreds of people who knew and loved David.

David was the youngest of three brothers, my father Charles the eldest, Robert in the middle. They grew up in Beverly Hills, their father a bookkeeper for movie stars and people who needed a bookkeeper, his most famous client Hedy Lamarr. The child movie star Jackie Cooper lived down the street and the Walton boys attended one of Jackie’s birthday parties when David was very young. The brothers graduated from Beverly Hills High, where my father met my mother, and David went to MIT, as did Robert, the alma mater of their father, while my dad broke with family tradition and went to UCLA after which he attended medical school in San Francisco.

Upon graduating from MIT, David returned to Los Angeles and went to work for his father as a bookkeeper for some years, and when his father semi-retired in the early 1950’s, David relocated with his parents and brother Robert, who was by then severely disabled, to Carmel and Monterey, which is when my firsthand memories of Uncle David begin.

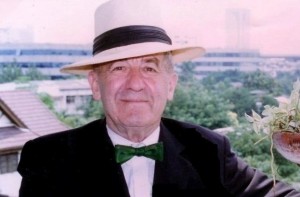

David was a handsome man, graceful and charming. In middle and old age he resembled the actor Alec Guinness to such a remarkable degree that after the first Star Wars movie came out, people frequently approached him thinking he was Obi-Wan Kenobi. I know this to be true because I was with David on two occasions when he was waylaid by star-struck people wanting Obi-Wan’s autograph.

David wore the same outfit every day of his life starting when he was in his early twenties. Unless he was backpacking in his beloved Sierras, he wore black shoes, black socks, black slacks, white dress shirt, bow tie, and black dinner jacket. In the privacy of his home he liked to wear a silk bathrobe. His bow tie was most often black, but occasionally plaid, the plaid of the Ross clan, which Uncle Bob discovered was a big part of our Scottish lineage. David told me that wearing the same clothes every day—his uniform as he called it—saved him time and trouble and money, made his suitcase light, and fulfilled his vision of himself as a kind of butler-at-large.

A butler? Yes. David told me that when he was eleven, circa 1937, he saw the movie My Man Godfrey, and thereafter knew who and what he wanted to be. The movie is a zany comedy starring the charismatic William Powell as a derelict who becomes a butler in the home of a wealthy and highly dysfunctional family, the female lead played by Carole Lombard. David told me that William Powell’s character Godfrey, the confidante and indispensable aide to everyone in the family, became David’s ideal for the kind of person he wanted to be; and to a remarkable degree David’s life reflected his adherence to the role of an indispensable servant, in butler’s dress no less.

In Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim, the young hero is known to his admirers as Little Friend of All the World, and that, too, describes Uncle David, for he had legions of friends around the world, many of them falling under his spell while being served by him in one or another of the famous eateries he opened in Monterey, first in the 1950’s and then again in the 1980’s.

The first place David opened (circa 1955) was a coffee house, the Sancho Panza, in downtown Monterey when Monterey was a still a sleepy little town and Cannery Row was boarded up and abandoned. Sancho Panza, you will recall, was the loyal servant to Don Quixote, and David was the loyal servant to the public that came to hang out in that now mythic café for the decade when it was a cultural epicenter for artists and renegades and sophisticates and regular folk of Monterey and Carmel and Pacific Grove, as well as a wonderful surprise for tourists and travelers from far and wide.

The Sancho Panza, according to David, was home to the second genuine Italian espresso coffee machine on the entire west coast of North America when he first opened his doors, the first such machine being in Caffé Trieste in North Beach, the founders of that famous coffee joint being David’s friends and through whom David got his machine. Henry Miller, Joan Baez, Alan Watts, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder, and Bob Dylan were among the many writers and artists and musicians who frequented the Sancho Panza, the coffee drinks legendary, as were the fruit frappes David concocted to go with yummy comestibles.

David would eventually open a little bookstore upstairs over the café, and in the early 1960’s David opened his second establishment The Palace on Cannery Row, which was one of the earliest sparks leading to the revival of that now aquarium-centric hot spot. The Palace was a beer and sandwich joint with a stage for live performers, and I regret I never got to experience The Palace in full swing. The Sancho Panza, on the other hand, was the highlight of our trips to visit my grandparents, and I would always have a peach or banana frappe and a cookie while hanging on Uncle David’s every word.

And while he was running the Sancho Panza and The Palace and performing in local theatre productions, David continued to be his brother Bob’s main caretaker, Bob having been paralyzed on the entire right side of his body as the result of a terrible car accident when he was in his mid-twenties. David was also a daily visitor to his parents’ house just up the hill from his café, his mother and father staunch Republicans and proud members of the John Birch Society, while the lefties and lesbians and Buddhists and artists gathered at the Sancho Panza to drink cappuccinos and revel in the Bohemian joint that David built.

Then in 1966, much to the shock and dismay of his many friends and followers, David announced he was selling both the Sancho Panza and The Palace and going to Vietnam to open USO clubs for the troops. David’s father, my grandfather, had recently died, and David had settled his mother into a nice apartment he shared with her on the beach in Monterey, and he arranged for people to do for Bob what he had been doing for Bob, and off he went to Vietnam.

“When I got off the jet in Saigon,” David told me, “and I was being driven to the site of the first club I opened, I felt deep in my bones I’m home. I’m finally home.” He came to realize that this feeling of being home was not so much about Vietnam as it was about Asia, for after a few years in Vietnam, David moved to Thailand and lived in and around Bangkok for many years. He came back to America fairly often to check on Bob and visit his many friends, but he was committed to living in Thailand where he was planning to build a retirement community and open a restaurant on an island owned by wealthy Thai friends.

I am, believe me, skating over the surface of David’s life, much of it unknown to me. When in 1978, I published my first novel Inside Moves, I let David know that Doubleday was throwing a publication party for me in Manhattan, and David sent me a roster of a dozen of his New York City friends he wanted me to invite. I did invite them and they all came out of loyalty to David, among them corporate executives, college professors, and penniless poets. One of the wealthy executives bought a dozen copies of my book and said as I signed them, “It is a great honor to meet the nephew of David Walton.”

“How do you know David?” I asked him.

“We go way back,” he said, winking mysteriously. “He’s a great man. One of the greatest.”

Then in 1984, just as David was about to open a Thai-American restaurant in Thailand, a friend called and offered him a restaurant location across the street from the brand new Monterey Bay Aquarium, and as David told me, “I couldn’t pass up the chance, so I brought my crew from Thailand and we opened the Beau Thai.” And that restaurant, known as David Walton’s Beau Thai, was soon famous and adored by locals as well as tourists, and David settled back into life in Monterey in his little beachside apartment, which he shared with two and sometimes three folks from Thailand.

No matter the season, David would take a daily plunge in frigid Monterey Bay before donning his uniform and heading off to the Beau Thai. Sadly, at the zenith of the Beau Thai’s popularity, tax trouble forced David to close the place, after which he returned to Thailand where he became entranced with the idea of moving to China, which he eventually did. David’s first home in China was an apartment in the enormous city of Chengdu where he lived for some years before moving to Xichang in the foothills of the Himalayas where he swam in Lake Qionghai, taught English to eager students (though he spoke no Chinese) and lived quite happily until he died. His sole income was from a pittance, less than eight hundred dollars a month, from Social Security, “Which is more than enough,” David told me, “to live quite well in Xichang.”

“I will cross over on my ninetieth birthday,” he said to me on several occasions, and though he died three years shy of ninety, knowing David as I do, I would not be surprised if he waits to cross over entirely until another three years have gone by, which would be fine with me because he was a wonderful spirit, a vibrant fun-loving soul who always encouraged me on my less traveled path, which was a great boon to me.

I have barely scratched the surface of David’s life in this telling, and I have at least a hundred good stories to tell about David, but that is nothing to the thousands, nay, tens of thousands of stories his many friends could tell about him, which supports my lifelong suspicion that there must have been more than one of this astounding fellow.

Here is one very telling story about David. When he was a young man, he drove up from Monterey in his famous yellow convertible Volkswagen bug to visit relatives in Oakland, and stopped at a florist’s shop to get flowers to bring to his cousins. He entered the shop to find the owners, a middle-aged couple, in crisis because their delivery person had suddenly walked off the job. Without a moment’s hesitation, David said, “I will be happy to deliver flowers for you,” which he did for the rest of that day and the next. He became fast friends with the couple, visited them many times over the ensuing years, they came to the Sancho Panza when in Monterey, and when the woman’s husband died, David helped the woman move to a commodious trailer on a lot in Vallejo, a lot and trailer, along with all the woman’s earthly possessions, that David inherited when she died.

David told me that story when I visited him in a tree house he’d built in a gigantic old pine tree in Pacific Grove on the property of a good friend. The tree house was full of books and things he’d inherited from his parents and various folks who loved him along his way.

“Take anything you want,” he said to me. “I’m not attached to any of it. But do let me have a look at what you take before you go and I’ll tell you the story behind it.”