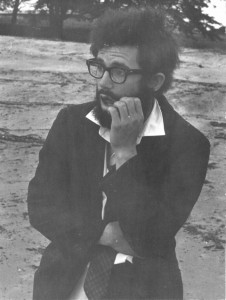

Todd 1969 photo by Richard Mead

(This article appeared in the Anderson Valley Advertiser March 2015)

Hey Nineteen, that’s ‘Retha Franklin

She don’t remember Queen of Soul

Walter Becker and Donald Fagen

Digging around for photos of my grandmother, I came across a black and white picture of me taken in 1969, a still shot from a student film made during my second and final year of college at UC Santa Cruz—when tuition was next to nothing. My decision to quit college was made easier than it would be today because housing in 1969 was cheap, work was easy to come by, and the economic obstacles to experimenting with being an artist were minimal, certainly compared to the economic realities of 2015.

In the photograph, my thick brown hair is going every which way, my kinky beard full and black, my black-framed glasses the same ugly frames millions of myopic young American men wore at that time. I am wearing a black suit and tie because in the film I play the part of a violin teacher, my student such a terrible player that his squawking music drives me first insane and then causes me to have a heart attack and fall to the sand.

For reasons never made clear to me, the violin lesson is taking place on a beach, the blond violinist short and fat and wearing only enormous white diapers. After I fall dead, the grinning violinist walks into the ocean and disappears under the onrushing waves. I saw the three-minute film several times in one night in the filmmaker’s dormitory room, a couple dozen young men and women gathered to eat chips and salsa and drink cheap wine and watch the opus.

The consensus, heavily influenced by the ingestion of illegal substances, was that the movie was a work of surpassing genius and the filmmaker destined for international acclaim. I have no idea where that filmmaker is today, but on that night, he was hailed as a god.

My roommate played the part of the diapered violinist in the film, and was in reality a tone-deaf violinist. When he practiced in our room during the day, everyone in the dormitory would flee to the library or forest or cafeteria. And on those few occasions when he dared played at night, angry people would pound on our door and threaten to kill him if he didn’t stop.

One of those angry people was a pre-med student living alone in the room directly below us. A clean-cut fellow with black-framed glasses, he always wore pressed beige slacks, a white dress shirt, a striped tie, and a beige sweater. He rose at dawn every day, showered, shaved, dressed, and then rushed to the cafeteria to wait for door to open so he could eat breakfast at seven, after which he would race to his Organic Chemistry lecture and lab.

I was often playing Frisbee in front of the dorm when this hardworking fellow returned from a long day of pre-med travails, and he would sometimes stop to watch us flinging the disc and say, “Don’t you guys ever study?”

One night at a dorm party, he got very drunk and grabbed a young woman who screamed bloody murder as she fought him off, and it took four of us to pull him away from her and subdue him. The next morning, he rose early, donned his uniform, and was first in line at the cafeteria.

Some months later, this dedicated pre-med student did not emerge from his room for breakfast or to attend classes. Nor did he emerge the next day. His door was locked and he did not respond to entreaties to come out. The campus police were alerted and they opened his door with a master key. The poor guy was sitting at his desk, unmoving, his Organic Chemistry textbook open in front of him. He was not dead. He was simply sitting there, his mind on hiatus.

The police took him to the campus medical clinic and from there he was taken to a hospital. Two days later, his mother and father arrived to get his things. His mother reminded me of the mother in the television show Leave It To Beaver—perfectly coiffed and with every stitch in place. His father looked just like him, only thirty years older, and wore the same pants and shirt and tie and glasses. Some of the guys helped them load his things into their car while a buddy and I played Frisbee.

The next day, two new guys moved into his room. One of them was a fanatical chess player, the other a jazz buff. They were both Sociology majors, rarely went to class, and thereafter John Coltrane and Herbie Hancock became staples of the quad.

It’s hard times befallen Soul Survivors

She thinks I’m crazy, but I’m just growing old

Walter Becker and Donald Fagen

I was under the spell of Nikos Kazantzakis for my two years in college. I read all his novels, and Zorba the Greek three times. To culminate my absorption of Kazantzakis, I was slowly working my way through his epic poem The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, a massive work divided into twenty-four rhapsodies and consisting of 33,333 seventeen-syllable verses.

The messages I kept getting from Kazantzakis were: Get faraway from academia, follow the dictates of your heart and intuition, beware the overly-analytical, strive, sweat, make love, make music, write, travel, gather stories, and become a master of at least one thing, two or three if possible.

I finished reading that gigantic poem a month before I was to return for my third year of college, and I wept as I read the last few pages. Odysseus, the Odysseus Kazantzakis imagined, had been my constant companion for two years, and now he was dead. The book had been a bridge for me between childhood and adulthood, as had those two years of college. Now it was time to hit the road and, as Kazantzakis suggested, see what kind of trouble I could get into.