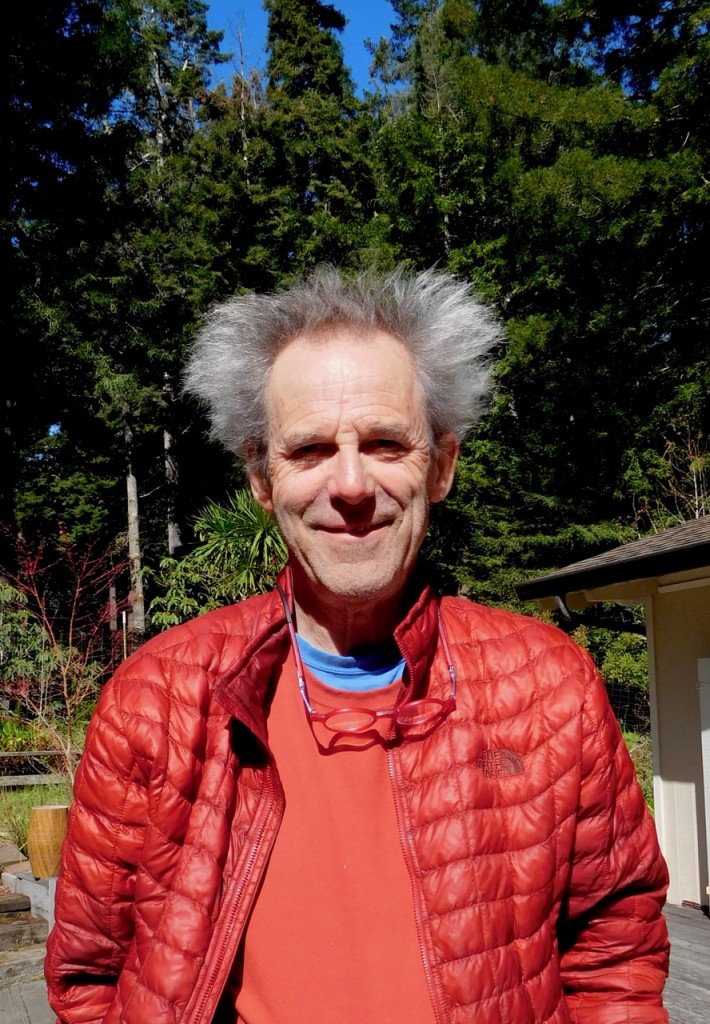

Shadow photo by David Jouris

I was sitting in the Mendocino Taqueria waiting for my tacos when a man and woman came in, the woman carrying a three-month-old baby boy who was being fussy and crying. The woman jiggled and bounced the baby and cooed reassuringly, but the baby was not to be consoled. The man ordered their supper and went to use the bathroom, and the baby continued to fuss and whimper despite the tender cajoling of his mother.

I smiled at the woman to communicate my support for her efforts to soothe her baby, and the baby saw my smile, locked eyes with me, and stopped crying. My eyes widened and I said “Hello,” to the baby, and the baby gurgled a reply, and we continued to look at each other for a minute or two until the mother turned away, breaking the connection between her baby and me. This breakage caused the baby to start fussing and whimpering again, which caused the mother to jiggle and bounce the baby again, but the baby was not to be consoled until his mother happened to turn toward me again, and the baby subsided into fascination with me and I with him—the baby’s mother unaware of what was causing him to stop fussing.

When I say “locked eyes” what may have happened, according to recent neurological discoveries, was that the baby’s mirror neurons and my mirror neurons engaged with each other, and this engagement created what some neuroscientists call a conjoined neurological system—the sharing of our two minds.

Mirror neurons are a fairly recent discovery, and there are different kinds of mirror neurons, and there is intense debate among psychologists and neurologists about how mirror neurons work, but what I’ve read about them has made me a devout believer in conjoined neurological systems.

I’m sure you’ve had many experiences similar to my hookup with that baby boy in the taqueria, and I have no doubt that conjoined neurological systems make possible the pleasure and sense of completeness that so many new mothers experience in relation to their babies, the feelings of satisfaction that so many parents experience while relating to their children, and the phenomenon of people falling in love with each other.

I’ve had thousands of such transcendental hookups with babies, children, dogs, cats, and other humans in my life, and now that I have read multiple texts about neurobiology and mirror neurons, I am hyper-aware of how quickly these mind melds can occur when I and my fellow animals are open to such unions.

According to Dan Siegel, a psychiatrist and neurobiologist, optimal human health—mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual—depends on frequent positive interpersonal brain hookups. Our brains and nervous systems—our minds—evolved specifically to interact with other brains. We are inherently cooperative animals, and when we don’t have enough interaction with other animals, our brains atrophy and die.

This is why solitary confinement in prison is so damaging to a person’s health and sanity. It is one thing to choose to be alone for a day or two or three, but to be forced into isolation with no hope of connecting healthfully and meaningfully with other people or animals or living things is truly terrible torture.

I am a social isolate, not by nature, but in response to my abusive parents who combined individual abuse of their children with aggressively disallowing my siblings and I to unite in order to weather the ongoing misery. This made it necessary for each of us to emotionally fend for ourselves, and as a result, all four of us became social isolates in our own unique ways.

When I chose to pursue writing as a career rather than becoming an actor, I was unaware that my tendency to isolate was the largest determining factor in that choice. I was not a gifted writer, but I was an excellent actor; yet after high school I chose to pursue writing instead of acting because my lifelong habit of self-isolation was too strong for me to overcome. Thus, as Gabor Maté discusses so compellingly: what began as a childhood coping mechanism became my habit, and my tendency to self-isolate, which was my salvation until I left home at seventeen, made group activities much more challenging for me than for people who grew up in families that supported and encouraged the healthy inclination to interact and cooperate and collaborate with others.

Despite my tendency to self-isolate, I have always been a person who other people, including complete strangers, feel comfortable confiding in, and I’ve often wondered why this is so. As the result of some experiments I’ve been conducting, I understand that when I interact with other people, I emanate the vibe of someone safe and enjoyable to talk to.

As the result of my reading about how our neurological system works, I know that most human brains are ready, one might even say eager, to hook up with other brains if, and this is a hugely important if, those other brains communicate: I’m friendly and want to interact with you so we can experience the pleasure and fascination of mind melding.

Prior to my recent experiments, I must have been unconsciously emanating this message. In my experiments, I consciously think (and feel) I’m friendly and want to interact with you so we can experience the pleasure and fascination of mind melding when I start up a conversation with someone in line at the bakery or I bump into someone at the post office or I engage with the checker at the grocery store.

The results have been astounding. Not only do nearly all randomly selected people open up to me as if I am a dear and trusted friend, but their bodies relax, their faces soften, and my body and face relax and soften, too. These physical and emotional changes occur so predictably in the course of our interactions, if I hadn’t read volumes of neurobiology I might think I’d stumbled on the trick of emotional hypnosis. But what I’ve learned is that humans are hardwired to connect in this way if given the opportunity.

We live in a society that produces highly defended people, defended internally and externally. But being so intensely defended is not our true nature. Our true nature, our genetic heritage, is to be closely connected—emotionally, physically, mentally, spiritually—with the other members of a band of people. We are designed to be part of conjoined neurological systems.

And when we meet others of our kind and we feel/hear/believe/trust that the other is friendly and wants to interact with us so we can experience the pleasure and fascination of mind melding, then our true natures are awakened.