Wade stops walking, looks around the neighborhood he’s lived in for forty-five years, and says, “What am I doing?”

A few minutes ago, he was sitting on the sofa in his living room staring at the big-screen television when his wife Mimi came home from the supermarket and growled, “Oh shit. I forgot the fucking milk.”

“I’ll walk down to Balducci’s and get a quart,” said Wade, rising from the sofa.

Then he walked to the front door, got his old brown leather jacket off the peg on the wall, put the jacket on over his faded blue shirt, tapped the back pocket of his brown corduroy trousers to make sure he had his wallet, jingled his right front pocket to make sure he had his keys, and walked out of the house into the late October afternoon, the pale blue Oregon sky sporting wispy white clouds tinged with pink.

Wade is sixty-eight, six-feet-tall, straight-backed and neither fat nor thin. His hair used to be black and is now mostly gray and turning white, and though he hasn’t had a haircut in over a year, his hair is not very long. Until a few years ago, before he became a recluse, the four words almost everyone used when describing Wade were handsome, friendly, funny, and generous. His father was from Montana, his mother from Brooklyn, and there are hints of his mother’s Brooklyn accent and tonality in Wade’s speech.

Mimi is sixty-five, a bountiful five-foot-four, and she walks with a noticeable limp, hip replacement surgery on the near horizon. Her once reddish brown hair is now silvery gray and cut shorter than Wade’s. Her parents were both from Boston, and though Mimi has lived in Oregon for most of her life, she sounds like a Bostonian.

Why did Wade look around his neighborhood and say, “What am I doing?” when he was a block from his house on his way to Balducci’s to buy a quart of milk?

Because for the last three years, whenever Mimi came home and complained of forgetting to buy something, Wade has never said, “I’ll walk down to Balducci’s,” though prior to three years ago, ever since he was in his twenties, he would walk to Balducci’s almost every afternoon to get an item or two that Mimi forgot to buy at the supermarket.

Or did she forget to buy the milk or a jar of olives or bananas? The regularity of her forgetting, and the inevitability of Wade getting up to walk those five blocks to the little neighborhood grocery store suggests that her forgetting was not forgetting at all, but part of a ritual she and Wade enacted to get him off the sofa and out into the world.

Wade was a high school Physics teacher for forty-one years, and Mimi, a high school administrator, would often find Wade sprawled on the sofa when she got home from work in the late afternoon; and she knew the slightest impetus would send him on his way to Balducci’s, a little trek he much preferred to zoning out in front of the television, and an enjoyable way for him to spend time with their children Diana and Michael who often accompanied him to Balducci’s and back.

And the reason Wade stopped getting up from the sofa and going out into the world when Mimi named the items she forgot to get on her way home from the high school where she is now vice-principal, is that three years ago their son Michael was killed in a car accident. Michael was forty-two when he died, and Wade might have been a crystal goblet dropped from a hundred feet in the air onto concrete, so shattered was he by Michael’s death.

∆

Wade is about to turn around and go back to his house when someone calls, “Wade. How you doing? Haven’t seen you in forever.”

For some reason, being hailed in this way causes Wade to look at the palm of his right hand and focus on the crease in his palm that palm readers call the life line; and he wonders why his life line is so much darker and more clearly delineated than the lines for fate and love and wisdom and marriage. Now he thinks of his mother for the first time in many years, his mother who read palms as a serious hobby.

Wade looks up from inspecting the palm of his hand, and here is Allan Wilder with whom he used to play golf every Saturday until three years ago. Allan is stout and good-natured and entirely bald and ten years younger than Wade. He is standing on the brick walkway leading to his front door, wearing a faded red Stanford sweatshirt and beige trousers and holding a red rake, the head of which is half-buried in a pile of gold and bronze maple leaves.

“Allan,” says Wade, his voice weak from three years of rarely speaking. “You look just like yourself.”

“So do you,” says Allan, dropping the rake and coming to shake Wade’s hand. “I missed you, buddy. I think about you all the time.”

“Still playing golf?” asks Wade, noticing how greatly Allan has aged in three years, some terrible sadness at work on him.

“Twice a week,” says Allan, beaming at Wade. “Remember what a terrible putter I was?”

“You took your eye off the ball,” says Wade, remembering how Allan would always glance at the hole a split second before he struck the ball. “You couldn’t help it.”

“Well I’m much better now,” says Allan, nodding emphatically. “When Joan left me two years ago, I put in a putting green in the backyard and now I make at least two hundred putts every day. I’ve trained myself to keep my eye on the ball until I hit it, and even after I hit it I keep looking at where the ball was. Like you told me to.”

“I told you to do that?” asks Wade, having no memory of ever suggesting anything to Allan about golf. “You put in a putting green? You’re kidding.”

“No, come see,” says Allan, beckoning Wade to follow him. “Astro turf.”

∆

Wade takes the putter from Allan and positions himself over a golf ball fifteen feet from one of several holes in the artificial surface; and everything about this moment feels wholly new yet entirely familiar to him—a dizzying combination of sensations. But what is even more remarkable to Wade is his absolute certainty that he is going to sink this putt, the hole he’s aiming for seeming as big as a manhole to him. And though he is tempted to tell Allan about how sure he is of making the putt, he defers to Allan’s insecurity about putting and says nothing as he strikes the ball and watches it speed across the green and drop into the hole.

“Wow!” exclaims Allan. “You’ve still got it, Wade. You’re a master.”

”One shot does not a master make,” says Wade, his mother coming to mind again, how after his greatest triumph in a high school basketball game she reminded him, “Today you win, tomorrow you lose. The important thing is to do your best.”

“You’ve always been such a great putter,” says Allan, dropping another ball in front of Wade. “Try the hole in the far right corner.”

Wade smiles sadly at Allan and asks, “Why did Joan leave you?”

“She fell in love with a guy she met at a conference on syntactical errors in the translation of Aristotle.” Allan shrugs. “A subject dear to her heart and far from mine.”

“You’re kidding,” says Wade, frowning at Allan. “Where was this conference?”

“At Harvard,” says Allan, nodding. “Maybe it was a symposium and not a conference, but in either case she fell in love with him and… that was that.”

“I’m so sorry, Allan,” says Wade, poised over the golf ball. “I know how much you loved her.”

“Hey…”says Allan, fighting his tears, “you can use this putting green any time you want. House goes on the market in April, but until it sells, come play.”

“I will,” says Wade, striking the ball and watching it roll across the plastic greensward to fall with a satisfying clunk into the farthest hole.

∆

After saying goodbye to Allan, Wade thinks about returning to his house and collapsing on the sofa, but the idea of getting a quart of milk for Mimi gives him a jolt of energy, so he carries on in the direction of Balducci’s.

But after another block, he is overcome with exhaustion and sorrow, so he sits down on the low brick wall in front of the Dorfmans’ house, the front yard bursting with roses—Susan Dorfman famous for her flowers.

Sitting with his back to the rampant blooms, Wade thinks about the last time he saw his son Michael alive. Seven months before Michael died, he came to Portland on a business trip. He lived in North Carolina with his wife Maureen and their two children.

During supper with Wade and Mimi, Michael and Wade got into a huge argument about Michael wanting to get a puppy. Michael and Maureen had just had their second child, and Wade was incensed that Michael would add a dog to Maureen’s life when she was already overwhelmed by the new baby and their four-year-old, while Michael was gone all day at work and forever going on long business trips.

“So what if he wanted a dog?” says Wade, clenching his fists and pounding his legs. “Why shouldn’t he have a dog? He loved dogs. We always had dogs. We got a puppy when he was a little boy. Why did I yell at him like that? What was wrong with me?”

“Wade?” says a familiar voice. “You okay?”

“Oh, hi,” he says, turning around and seeing Susan Dorfman standing a few feet away from him, her roses ablaze behind her.

Susan is tall and willowy, nearly as tall as Wade, her blue eyes reflecting the turquoise of her dangly turquoise earrings and her necklace of turquoise stones and her turquoise blouse and turquoise jeans.

“I heard you shouting,” she says, sitting down beside him and gazing at the houses and trees across the street. “I’ve lived here for forty-two years and never sat here until now. What a lovely view.” She taps his shoulder. “Hey, I just remembered. You helped me build this wall. You taught me how to lay bricks.”

“We were in love with each other,” he says, the long-unspoken truth coming out as easily as if he’d told her it might rain. “But we were both happily married. Or… thoroughly married. So what could we do?”

“Nothing we were willing to do,” she says, putting her arm around him. “I’m so glad you told me, Wade. I’ve always wanted to know. I mean… I knew I loved you, but… and I was pretty sure you were in love with me, especially after our kiss on New Year’s Eve. Remember? The year I turned thirty and you turned thirty-three?”

“A dangerous kiss,” he says, nodding. “A marvelous kiss. Maybe the best kiss I’ve ever had. Unfortunately, Mimi saw us kissing and she was furious about it for years and years, though she was having affairs long before you and I kissed that night.” He sighs. “I never had an affair. Just… never did.”

“We were so young,” says Susan, sighing, too. “Still trying to tame our lusty natures.”

“Did you ever have affairs?” he asks, gazing at her. “Something tells me you didn’t.”

“No,” she says wistfully. “Mel did. But not me.”

“The older I get the more ridiculous it seems that we weren’t lovers, you and I.” He smiles at her. “But even more ridiculous is that we were not better friends, because beyond the sexual attraction, you have always been one of my very favorite people. I could talk to you about so many things Mimi had no interest in. Because you were interested in everything I was interested in. At least I thought you were.”

“Oh, I was,” she says, nodding. “You and I were interested in all the same things. That’s why I always made a beeline for you at parties. Mel didn’t give a hoot about roses or gardening or art or music or… much of anything I cared about.”

“He liked golf,” says Wade, remembering how furious Mel would get when Wade beat him, which was not often.

“And gambling,” says Susan, nodding. “I’d be rich today if not for his gambling.”

A trio of cars go by—various genres of music wafting from their windows.

“So… how are you doing?” asks Susan, switching from having her arm around his shoulders to holding his hand. “About Michael?”

“I’ve been comatose since he died.” Wade closes his eyes. “I died when he died, only I didn’t die. I’m still here.”

“I can’t imagine what I would do if any of my kids or grandkids died before me.” She tightens her grip on his hand. “When Mel died I wasn’t that sad. I mean… I missed him, but… not really. We were never very happy together after the first few years. But if Molly or Jason or any of their children were to die… I can’t imagine going on living.”

“But I did,” says Wade, resting his head on her shoulder. “If you can call it living. I’ve been no good to Mimi or Diana or Maureen or the grandkids or anyone. I’ve been frozen.”

“You want some tea?” she asks, the air growing nippy. “Thaw out a little?”

“No, thank you, Susan,” he says, kissing her cheek. “I think I already am thawing out a little. I’m going to Balducci’s to get a quart of milk. You want anything?”

“Balducci’s isn’t there anymore,” she says, blushing from his kiss. “Come for tea tomorrow. Okay?”

“Okay,” he says, eager to see what has taken the place of Balducci’s.

∆

As Wade nears the corner where Balducci’s used to be, his brain tricks him with a fleeting image of the little grocery store that dissolves into a spanking new café fronted by a red brick terrace on which large blue umbrellas rise from round tables surrounded by green plastic wicker chairs, the sign above the café entrance proclaiming FRACTAL BREW in large white san serif letters on a black background.

Wade approaches the new café feeling sad about the disappearance of the little grocery store that was a foundational component of his life for forty-five years, but also feeling mighty curious about FRACTAL BREW because he was, after all, a Physics teacher who was madly in love with fractals. He had a cat named Fractal. For thirty years he oversaw an after-school club for Math and Physics geeks called Imagining Fractals, the club T-shirt black with Infinitely Self-Similar writ in large white letters on both the front and back of the shirt.

“But why did they have to replace Balducci’s?” he says to no one. “Where will I buy things that Mimi forgets to buy?”

He enters FRACTAL BREW and marvels at the gleaming hardwood floor, the chrome and red-leather booths, the stainless steel table tops, the many and voluble customers, the black marble counter, and the sparkling kitchen beyond.

“I feel like Rip Van Winkle,” he says, stepping up to the counter and smiling at a young Eurasian woman in a fetching white dress, a red rose in her glossy black hair.

“I don’t think we have that,” she says, pointing at the big chalkboard on the wall. “I’m new here, but I’m pretty sure those are the only coffee drinks we serve, and I know we don’t have that kind of beer.”

“I meant the guy who wakes up after sleeping for twenty years and finds everything changed.” Wade studies the young woman and guesses she is twenty-three, the age of his granddaughter Lisa, Diana’s oldest child. “Would it be possible for you to sell me a quart of milk? Whole milk, not skim.”

“I’ll check,” she says, leaving the counter and sauntering into the kitchen.

Wade looks around the room and is struck by how familiar everyone seems, as if forty of his former students are having a reunion.

“Here you are,” says the young woman, returning to the counter with a quart container of milk. “That will be four dollars and twenty-five cents.”

“Thank you so much,” says Wade, handing her a five-dollar bill. “Keep the change. Did you know this used to be a little grocery store? Balducci’s. I must have bought five thousand quarts of milk here. Maybe ten thousand.”

“Awesome,” she says quietly as she puts the quart of milk into a snazzy black bag with FRACTAL BREW printed on both sides. “There’s a photograph of Balducci’s on the wall by the front door. I thought maybe it was an Italian restaurant.”

“No,” says Wade, shaking his head. “Just a little grocery store.”

∆

Instead of going home the way he came, Wade wanders through the commercial district bordering his neighborhood, and he’s glad to see Rick’s Automotive is still here, Hobart’s Used Books is still here, Levant’s Ice Cream Shoppe is still here, and Kim’s Dry Cleaners is still here.

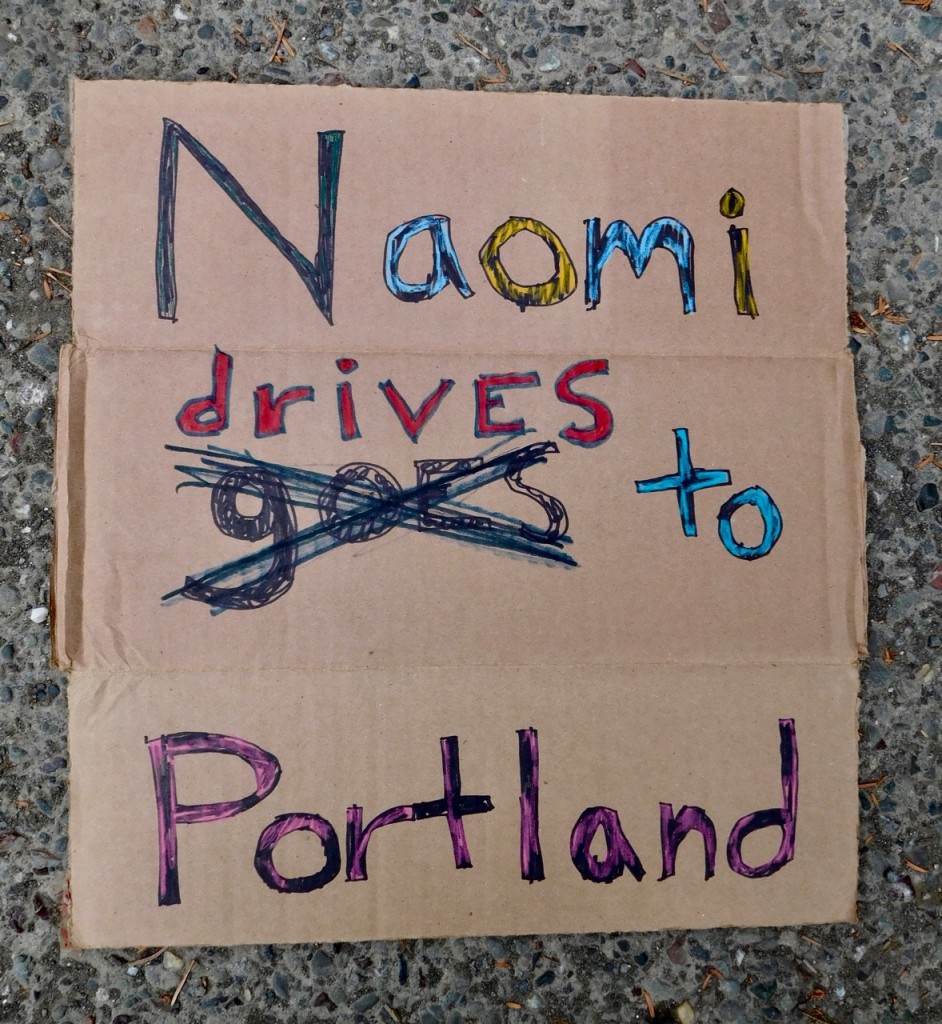

When he arrives at the corner of Delaware and 57th Avenue where he usually crosses Delaware to re-enter his neighborhood, he finds a woman and a boy squatting with their backs against the wall of a shuttered storefront, a flimsy cardboard box on the sidewalk in front of them. The woman is in her thirties and wearing a dirty orange jacket and greasy brown trousers. The boy is seven or eight and wearing a filthy gray sweatshirt and grass-stained blue jeans.

Wade gets out his wallet, intending to give the woman five dollars, when the boy says in a croaky voice, “Puppies for sale. You wanna buy a puppy?”

“Puppies?” says Wade, the word striking deep into his heart.

“Only two left,” says the woman, her voice croaky, too. “The mother is a Black Lab, and we’re pretty sure there was more than one father. We know a Dalmatian got to her, but we’re not sure who else.”

Wade peers down into the cardboard box and sees two little brown blobs of fur, his vision obscured by tears. “How much?” he says, sobbing.

“Ten bucks each?” says the woman, jumping to her feet. “You want one?”

“Two,” says Wade, handing her all the money in his wallet, seventy-eight dollars. “I want both of them.”

∆

Darkness is falling when Wade gets home with the quart of milk from FRACTAL BREW and the cardboard box containing two puppies. He finds a note on the kitchen counter from Mimi saying she’s gone to her yoga class at the YMCA and will be home at nine.

He puts the milk in the refrigerator and picks up the two puppies, one in each hand, and they wiggle and whimper and one of them pees on him.

∆

When Mimi comes home, she finds Wade’s car parked in the driveway instead of in the garage, and when she enters the house, she is startled to see the big-screen television gone from the living room. She hears Wade laughing in the garage, so she hurries through the kitchen and opens the inside door to the garage, and here is Wade sitting on the floor playing with two adorable puppies.

The sight of Wade with the little dogs makes Mimi furious. “Are you insane?” she screams. “Getting puppies at your age? You could drop dead any day now and I’ll be saddled with your fucking dogs.”

Wade looks at her and says calmly, “I picked up a quart of milk for you. And if you don’t want to live with a man with dogs, we’ll get divorced.”

“Divorced?” she yells. “We’re not getting divorced. Just get rid of the dogs.”

“Mimi,” he says, taking a deep breath. “Your yoga class got out at six. And then you went to your lover’s house for three hours and now you’re home. Did you think I didn’t know about your affairs? I’ve always known. Since way back when. You must have known I knew. Yoga classes don’t last four hours. Lunch dates don’t last five. Maybe I should have divorced you the first time you cheated on me, but the kids were so little, and… then later, I don’t know, I came to accept what you were doing and decided to stay with you until the kids went to college. But when they were gone, I felt too old and afraid to start a new life without you, so I just went along with things. But when Michael died…” He holds back his tears. “When Michael died and you didn’t change the pattern of your life even a little to spend more time with me, I thought if I ever recovered from my terrible depression, I would ask you to be my wife again and not someone else’s wife. And if you won’t do that for me, for us, then I and my dogs will go elsewhere and start a new life.”

“And the house?” says Mimi, never having imagined Wade would be the one to suggest divorce. “We would sell the house?”

“Or you can buy me out,” he says, allowing himself to cry.

“I would like to do that,” she says, looking away from him. “I have four more years until I retire and I’d like to stay in this house until then and possibly longer.”

“So be it,” he says, smiling through his tears. “I want you to be happy. That’s all I’ve ever wanted for you.”

∆

The next morning, Wade wakes in the bed in the room that was Michael’s room when Michael was a boy and a teenager, and Wade’s very first thought is of the puppies waiting for him in the garage, how they need to be fed and petted, need to be taken out into the backyard to pee and poop and run and play, need to be loved.

And the thought of being with those marvelous little dogs propels Wade out of bed as he has not been propelled since he was a young man and every day was a glorious adventure.

fin