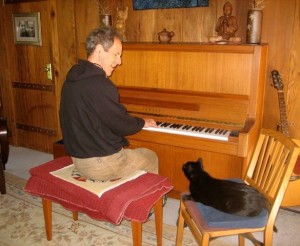

Cat & Jammer photo by Marcia

My new book of essays and memories Sources of Wonder has garnered some wonderful feedback from readers, with two correspondents saying they were especially taken with my memoir Playing For Capra. So here for your enjoyment is the true story of my meeting Frank Capra, this memory first published nine years ago.

Marcia and I recently watched the Israeli movie The Band’s Visit about an Egyptian police band spending the night in a godforsaken Israeli settlement. Seeing this remarkable film coincided with my struggle to write about the time I played piano for Frank Capra, the famous movie director.

Why the struggle? Because the story of playing piano for Capra is entwined with my dramatic rise and fall as a professional writer nearly thirty years ago. By the time I played piano for Capra in 1982, I had gone from living on pennies in the slums of Seattle to being the toast of New York and Hollywood, and back to barely scraping by in Sacramento, all in the course of a few dizzying years.

Capra, despite his many triumphs, was a Hollywood outsider. Having succeeded brilliantly under the protection of movie mogul Harry Cohn, Capra made movies he wanted to make, which were rarely what his overlords desired. In that regard, Capra was my hero. I had failed to build relationships with the powerful producers of American movies and books despite the many opportunities my early success provided me. I was young and naïve, and I believed that great stories and great screenplays would sell themselves. To my dismay, I experienced over and over again that quality and originality meant less than nothing to those who control our cultural highways. But I didn’t want to believe that, so I burned a thousand bridges.

Capra knew all about what I was going through, for he and his movies, despite their popularity with moviegoers, often received muted support from the power brokers. Why? Because he was unwilling to compromise the integrity of his visions. Indeed, he made movies about those very conflicts: integrity versus corruption, kindness versus cruelty, generosity versus greed, and originality versus imitation.

Capra’s autobiography, an incomparable history of Hollywood from the days of silent movies until the 1960s, was one of my bibles. In recent years, a confederacy of academic dunces has tried to discredit Capra’s recollections, but their pathetic efforts only amplify Capra’s importance.

So there I was in 1982, hoping to resuscitate my collapsing career, when we heard that Capra was going to speak at a showing of his classic It’s A Wonderful Life in an old movie house in Nevada City.

In 1980 a movie had been made of my novel, Inside Moves. Directed by Richard Donner with a screenplay by Barry Levinson, the movie—a Capraesque dramatic comedy if there ever was one—Inside Moves starred John Savage and launched the careers of David Morse and Diana Scarwid, who received an Oscar nomination for her performance in the film. Sadly, just as Inside Moves was being released, the distribution company went broke and the film was never widely seen. I was then hired by Warner Brothers to write a screenplay for Laura Ziskin (Pretty Woman, Spiderman) based on my second novel Forgotten Impulses, which was hailed by The New York Times as one of the best novels of 1980, but then Simon & Schuster inexplicably withdrew all support for the book and the movie was never made.

Indeed, as I drove from Sacramento to Nevada City with my pals Bob and Patty, I was in a state of shock. My previously doting movie agents had just dropped me, Simon & Schuster had terminated the contract for my next novel Louie & Women, and I had no idea why any of this was happening. Yet I still believed (and believe to this day) that my stories would eventually transcend the various obstructions and be read with joy by thousands of people—a quintessential Capraesque vision of reality. And I was sure Capra would say something in Nevada City that would help me and give me hope.

We arrived in the quiet hamlet in time to have supper before the show. We chose a handsome restaurant that was empty save for a single diner. On a small dais in the center of the room was a shiny black grand piano. The owner of the restaurant greeted us gallantly, and to our query, “Where is everybody?” replied, “You got me. We were expecting a big crowd for Capra, but…” He shrugged. “That’s show biz.”

Our table gave us a view of the piano and our elderly fellow diner, who we soon realized was Capra himself. Waiting for no one, eating slowly, sipping his red wine, the old man seemed to lack only one thing to complete the perfection of his moment: someone to play a sweet and melancholy tune on that fabulous piano. And I was just the person to do it if only the owner would allow me the honor.

I made the request, and it was granted. Frank was done with his supper by then and having coffee. I sat down at the piano and looked his way. He smiled and nodded, directing me, as it were, to play. We were still the only people in the restaurant, the room awaiting my tune.

I played a waltz, a few minutes long, something I’d recently composed, a form upon which I improvised, hoping to capture the feeling of what was to me a sacred moment.

When I finished, Frank applauded.

I blushed. “Another?”

Frank nodded. “Can you play that one again?”

“Not exactly, but close.”

He winked. “Perfect.”

So I played the tune again, longer this time, and slower at the end. Frank smiled and tapped his coffee cup with his fork. I approached him and told him we’d come to watch his movie and hear him speak.

He said, “Thank you. I love your music.”

His anointment of my waltz would have been more than enough to fulfill my wish that he say something to help me and give me hope. But the best was yet to come.

Capra’s genius was comprehensive. His best films are not only beautifully written and acted, they are gorgeous to behold. It’s A Wonderful Life was made when the art of black and white cinematography was at its apex, and we may never again see such artistry—many of the secrets of the black and white masters lost to time.

We marveled and wept at Capra’s masterwork, and then a nervous moderator gave Capra a succinct introduction and the old man took the stage. He thanked the crowd for coming and took questions—questions that made me despair for humanity.

The worst of the many terrible queries was, “Do you think you’re a better director than Steven Spielberg?”

“Different,” said Capra, pointing to another raised hand.

And then came the one meaningful question of the evening. “Your humor seems so different than the humor of today. Why is that?”

“Humor today,” said Capra, “for the most part, is pretty mean-spirited. We used to call it put-down humor, and we consciously avoided that. With Wonderful Life, you’re laughing with the characters because you identify with them, which is very different than laughing at someone.”

The inane questions resumed, and finally Capra could take no more. He waved his hands and said, “Look, if you want to make good movies, and God knows we need them, you have to have a good story. That’s the first thing. That’s the foundation. And what makes a good story? Believable and compelling characters in crisis. That’s true of comedy or drama. And the highest form in my opinion is the dramatic comedy, which has become something of a lost art in America. Then you need to translate that story into a great script. And I’m sorry to tell you, but only great writers can write great scripts. So start practicing now. And when you think you have that story and that script, get somebody who knows how to shoot and edit film, and make your movie. And when you finish, make another one. And if you have talent, and you persist despite everybody telling you to quit, you might make a good movie some day. Thank you very much.”

Which brings us back to The Band’s Visit. Capra would have loved those characters and their crises, and though he never in a million years would have made such a movie, his influence is unmistakable.