(This essay originally appeared in the Anderson Valley Advertiser March 2011)

“As the heavens are high and the earth is deep, so the hearts of kings are unsearchable.” Book of Proverbs 25:3

“Have you seen The King’s Speech?” asked a friend.

“Marcia has and loved it,” I replied. “I’m waiting for it to come out on Netflix.”

My wife Marcia and I are on the two-movies-a-month plan, and we often don’t find the time to watch even that many.

“Of course,” continued my friend, “they’ve taken great liberties with the historical facts. I read one article that said the movie isn’t even close to the truth and another that said it has some truth in it, but not much.”

“The only way to speak the truth is to speak lovingly.” Henry David Thoreau

Historical facts. Hmm. When I was attending UC Santa Cruz in the late 1960’s (and I really did do that) Norman O. Brown came to teach at our newborn college. His course Myth & History was open to undergrads, so I signed up to hear what the famous man had to say. Who was Norman O. Brown? Having taken his Myth & History class, and having spent a few hours blabbing with Norman about this and that, I think he would have been amused by the question. Why amused? Because the central theme of his course was that myth and history are inextricably entwined; history being mythologized the moment that highly subjective reporter known as a human being attempts to put into words what he or she thinks may have happened.

Before I tell you a little more about Norman O. Brown, I would like to recount a scene from Nikos Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation of Christ, the novel, not the movie. The Norman I remember (which is probably a very different Norman than the Norman other people remember) would have appreciated this digression because his lectures were composed entirely of digressions that would then double back on themselves and culminate in conclusions that, depending on each listener’s perspective, made some sort of larger sense. Or not.

“Great things happen when God mixes with man.” Nikos Kazantzakis

So…in The Last Temptation of Christ there is a memorable scene in which Jesus and his disciples are sitting around a campfire after a long day of spreading their gospel, when Matthew, a recent addition to the crew, is suddenly impelled by angels (or so he claims) to write the biography of Jesus. So he gets out quill and papyrus and sets to work transcribing the angelic dictation; and Jesus, curious to see what’s gotten into his latest convert, takes a peek over Matthew’s shoulder and reads the opening lines of what will one day be a very famous gospel.

Jesus is outraged. “None of this is true,” he cries, or words to that effect. And then Judas (I’m pretty sure it was Judas and not Andrew) calms Jesus down with a Norman O. Brown-like bit of wisdom, something along the lines of: “You know, Jesus, in the long run it really doesn’t matter if he writes the truth or not. You’re a myth now, so you’d better get used to everybody and his aunt coming up with his or her version of who you are.”

Kazantzakis, trust me, wrote the scene much more poetically and marvelously than the way I just recounted it, but…

“All good books have one thing in common. They are truer than if they had really happened.” Ernest Hemingway

Back to Norman O. Brown. In the late 1960’s, Norman was among the most famous pop academic writers in the world. Not only had he written Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History, which made him famous, he had just published (in 1966) Love’s Body, a mainstream and academic bestseller exploring the impact of erotic love on human history; or was it the struggle between eroticism and civilization? In any case, here is one of my favorite blurbs from the hundreds of reviews that made Love’s Body so famous in its time. I will digress again (thank you, Norman) by saying if any book I ever publish gets a blurb even remotely as stupendous as the following, and said blurb appears in, say, the San Francisco Chronicle or even the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, drinks are on me.

“Norman O. Brown is variously considered the architect of a new view of man, a modern-day shaman, and a Pied Piper leading the youth of America astray. His more ardent admirers, of whom I am one, judge him one of the seminal thinkers who profoundly challenge the dominant assumptions of the age. Although he is a classicist by training who came late to the study of Freud and later to mysticism, he has already created a revolution in psychological theory.” — Sam Keen, Psychology Today

The myth and history web site known as Wikipedia says that Norman was a much-loved professor at UC Santa Cruz where he taught and lived to the end of his days (he died in 2002, or so they say). Wikipedia also reports that Norman had the nickname Nobby, which I would like to say I gave him, but I did not. At least I don’t think I gave it to him. On the other hand, I might have given it to him because that was not his nickname when I knew him, so it must have been affixed after I knew him. Thus we might say, “After I got through with him, he was known as Nobby.” That does sort of sound like I’m responsible for his nickname. You decide.

“Personality is the original personal property.” Norman O. Brown

Here are a few true stories about Norman that might as well be myths.

Norman loved to fool around with the order of letters in words and the order of syllables in words and the order of words in phrases. For instance, he began one lecture by…

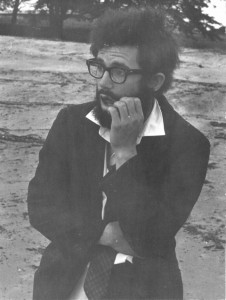

But first of all, here’s a snapshot of Norman in 1968: a portly white man of medium height with curly brown hair. I wouldn’t say his hair was unruly, but it was certainly not ruly. Is ruly a word? If not, then from whence came unruly? These were the kinds of questions Norman would ask of us, his audience, and not answer. On second thought, his hair was unruly. In either case, he would cast his questions upon his waters, he the fly fisherman, we the trout finning below the surface of his stream of consciousness, and he would allow the flies (the questions) to drift along above us for a time to see if we might rise to the bait. If no trout rose, he cast again.

Norman had voluptuous lips and frequently wept in front of us, moved by something he felt, or moved by inner demons we could only guess at, or moved by God knows what (if you subscribe to the myth of God.) I knew several people (mostly guys) who were so freaked out by how fragile and vulnerable and weird Norman seemed to them that they dropped the class after the first couple lectures.

“Freedom is poetry, taking liberties with words, breaking the rules of normal speech, violating common sense. Freedom is violence.” Norman O. Brown

One day (getting back to Norman’s playing with the order of letters in a word) he stood (wearing a brilliant white Mexican wedding shirt tucked into fine purple corduroy trousers, his feet shod in black sandals, his toenails painted red) with his back to the audience for the first five minutes of his presentation. People began to squirm; a few walked out; and several more were about to walk out when Norman turned to face us. He ran his fingers through his unruly hair three or possibly four times, took three (I’m absolutely sure it was three) tentative steps forward, touched the tips of the fingers of his left hand to the tips of the fingers of his right hand, and gazed at this collision of digits as a lover might gaze at her beloved, or as an autistic person might stare at her fingers, and then he pursed his voluptuous lips, raised his eyes to the audience, and said so quietly we had to strain to hear, “Roma.”

Then he swallowed, licked his lips, touched his fingertips together again as described above, licked his lips once more, and repeated, “Roma.”

I looked down at my notebook and saw that I had written Roma twice. And between the first and second Roma I had unwittingly drawn a heart.

Then I looked at Norman (I usually sat in the seventeenth row, having a particular fondness for that number) and he said, “Roma spelled backwards is…”

He waited a moment for us to begin to figure it out for ourselves, and then concluded, “Amor.”

“‘Tis as human a little story as paper could well carry” James Joyce from Finnegan’s Wake

Norman began another of his lectures mid-thought and mid-sentence referencing James Joyce’s novel Finnegan’s Wake. I could not, for the life of me, discern when Norman’s sentences ended or began or even if he was speaking in sentences. People ran for the exits as if a fire alarm had sounded. Soon there were only a few of us remaining in the vast lecture hall, Norman rambling on, his tired face alight with what might have been happiness or possibly incredulity to have struck such a rich vein of…something; and I gave up trying to understand him. I simply surrendered to his sound and subtle fury, and fell into a trance from which I did not emerge until…Norman’s voice rose to a girlish crescendo, fell silent for a momentous moment, and finished basso profundo with: “Finnegan’s Wake. Fin! Again! Wake!”

“Hearasay in paradox lust” James Joyce from Finnegan’s Wake

It was following Norman’s fifth or sixth or seventh lecture that I went to his office to show him a four-page play I’d written, a dumb show, a drama without words inspired by something he’d been harping on for a couple lectures. “The slave becomes the king becomes the slave.” In my dumb show, which, come to think of it, might have been choreography for a ballet, I was exploring passive aggression and aggressive passivity and the pitfalls of passion and the pratfalls of sexual positions, and (being nineteen) I thought the play was way cool, and I suspected that if anyone on earth would appreciate my play it was Norman.

I went to his office. He was sitting at his desk, weeping. He dried his eyes, rose to shake my hand, and invited me take a seat. I told him I was taking Myth & History. He said he recognized me. He said I often frowned ferociously at things he said, after which I would scribble furiously in my notebook. He said he often wondered which part of what he had just said made me frown. I said I was unaware of my ferocious frowning but wasn’t surprised to hear I frowned ferociously because ferocious frowning was my father’s habit, too. Norman said the older he got the more he reminded himself of his father, and also of his mother.

I then blurted that I found him captivating and perplexing and thought I was probably not consciously getting most of what he was trying to convey but I was apparently unconsciously getting some of it because he had inspired me to write a short play, which I then handed him. He read the pages, avidly, or so I like to think, then read them again. Then he looked at me and blinked appreciatively. “Yes,” he gushed. “The violence of Eros the inadequacy of the nuclear family to accommodate the sexual divergences of male and female energies of young and old I love the mother becoming lovers with her daughter’s lover only to discover her daughter’s lover is her father transformed. You’ve read Graves, Durrell, Duncan, Camus, Beckett. What do you want to do?”

“I want to write epic poems disguised as novels.”

He frowned gravely and pointed with the fingers of his right hand at the air just above my head. “A path of great danger,” he intoned, wiggling his fingers to incite the spirits. “Don’t be afraid.”

Todd lives in Mendocino where he prunes fruit trees, plays the piano, and writes essays and fiction. His web site is Underthetablebooks.com