Halloween 2025 was the twentieth anniversary of my arrival in Mendocino. My friend Bob Smith drove the big moving truck from Berkeley, and I followed him in a little old Toyota station wagon I’d just bought from a friend. I hadn’t had a car in seventeen years, but I would need one for my new life in these hinterlands.

We arrived at the house I was renting a few miles to the east of town just as darkness was falling, and my landlord greeted us with the news that she had belatedly discovered her previous tenants were secret smokers and she was having the place thoroughly detoxified before I moved in. She had arranged for us to spend the night at the Mendocino Hotel until I could move in the next day, and when we arrived at the hotel on Main Street there were several little kids in costumes trick-or-treating in the lobby.

The next day we moved my stuff, including my piano, out of the big truck into my new digs, and my new life began. I was fifty-six and knew almost no one in Mendocino, but trusted I would eventually find my way into the society here.

Twenty years later, the Mendocino Hotel is closed and crumbling, bought buy a large corporation in no hurry to re-open the once thriving hotel. Large corporations have bought many of the inns and hotels in the area in the last decade, many of the stores in Mendocino are vacant, and many of the houses in and around Mendocino are owned and left vacant by people who purchased the houses as investments and don’t want to bother renting them, which exacerbates the already deplorable rental situation.

Even so, Mendocino is mobbed on weekends and in the summer by visitors from near and far, though the town these visitors walk around in is nothing like the town I moved to twenty years ago. The legalization of marijuana ended an era here when many people made lots of money in that illegal trade, and all that cash fueled the local economy in a very big way for several decades. On the heels of legalization and the collapse of the local marijuana economy came the pandemic, which caused many shops and local businesses to close while creating our new retail reality in which most people are now habituated to buying things online rather than from small retailers.

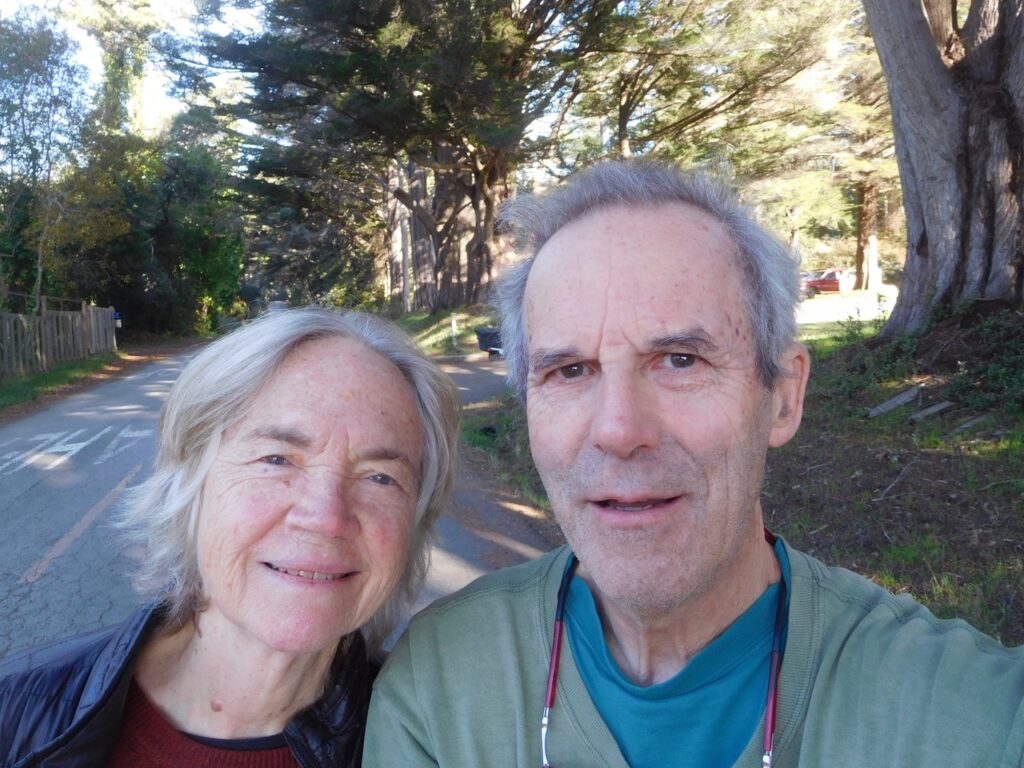

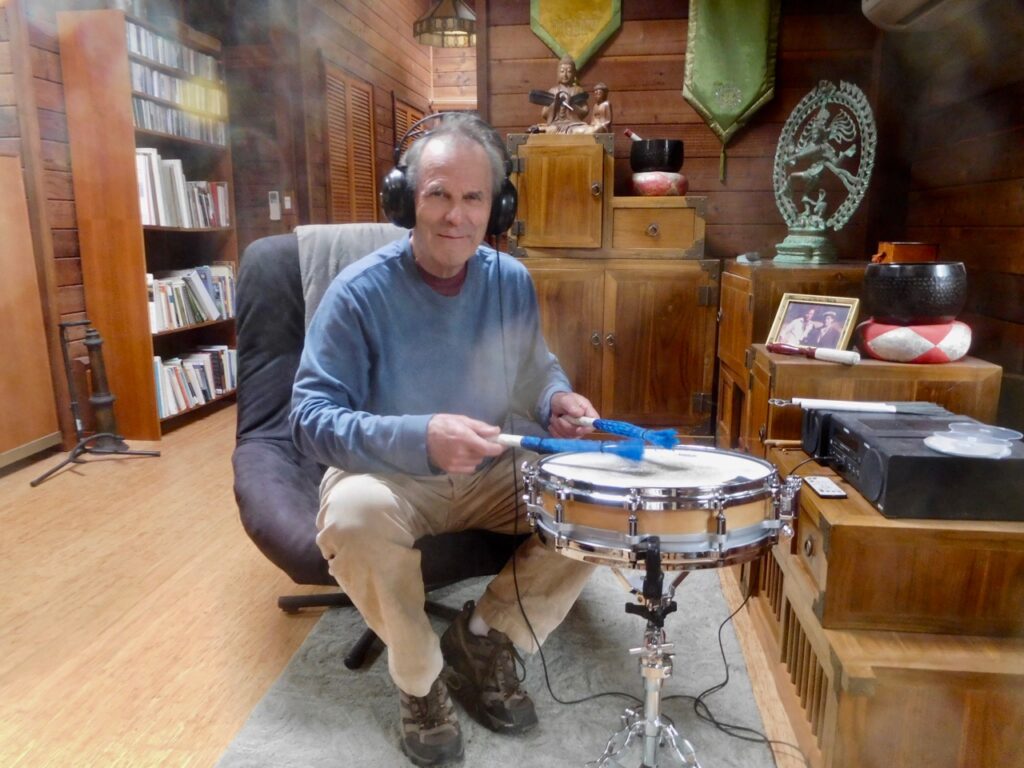

In my twenty years here, nineteen of those years with Marcia as my loving companion, I’ve written sixteen novels and dozens of stories and hundreds of songs. And I’ve posted a thousand blog entries, most of which are archived and accessible to you. I’ve learned to grow things in big tubs, having finally conceded defeat to the redwood roots that make growing things in the ground in our neck of the woods nearly impossible.

And, of course, I’ve seen the rise of the cell phone and social media culture, which I have nothing to do with except as an observer from afar. That new media culture, more than anything in my life, has made me feel like a stranger in a strange land.

When I was in my early twenties and living in a commune in Santa Cruz, I and a few of my commune mates made a trip up to Mendocino, circa 1973, to pick apples at a farm somewhere around here, and I loved this area so much I vowed to one day live here. My vow took thirty-three years to become reality, and I have now lived in this lovely part of the world longer than anywhere else I’ve lived during this incarnation.

fin