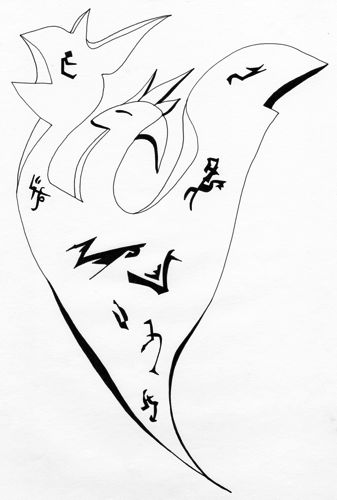

Ganesha photo by Marcia Sloane

(This article appeared in the Anderson Valley Advertiser September 2015)

“It has long been an axiom of mine that the little things are infinitely the most important.” Arthur Conan Doyle

Ganesha, also known as Ganapati and Vinakaya, is the male Hindu god with a human body and head of an elephant. His Rubensesque androgynous form is most often represented with four arms, each arm with a five-fingered hand, though some drawings and statues of Ganesha have as few as two arms and as many as twenty. Revered as the remover of obstacles, the patron of arts and sciences, and the deva of intellect and wisdom, he is also the patron deity of writers.

I knew nothing about Ganesha until nine years ago when Marcia and I got together, and Marcia revealed she was a devotee of the chubby multi-talented deity. She owns two small statues of Ganapati, one a handsome two-armed drum-playing fellow carved from wood, and the other an alluring six-armed dancing guy made of brass.

A remover of obstacles is my kind of deity, so with Marcia’s permission I placed her wooden Ganesha on top of my upright piano where he shares the lofty plateau with two statues of Buddha, one a happy standing fatso, the other a mellow lotus-positioned fellow with his thumbs and fingers touching each other in an intriguing mudra. The only other idol atop my piano is a tiny glass baseball player currently stationed in the shadow of Ganesha—my last gasp plea for the removal of the Dodgers from the path of our floundering Giants.

The more I learn about Ganesha, the more I like him, and when we recently removed the obstacle of an unsightly outhouse from a cirque of redwoods viewable from the eastside windows of our house, we decided to look for a large statue of Ganesha to stand in the grotto previously occupied by the ugly pooper.

And lo we were directed to Sacred Woods in Noyo Harbor in Fort Bragg, an impressive yard containing hundreds of statues imported from Thailand and Indonesia by Rachelle Zachary, the owner of Sacred Woods. After a delightful hour of statue shopping, we settled on an exquisite four-and-a-half-feet-tall white-stone statue of the elephant-headed god, hand-carved by a Balinese master, and a few weeks later the weighty objet d’art was delivered to our south-side deck.

Our plan was to have the redwood trees surrounding the proposed location for the statue limbed up before we engaged a trio of strong men to transport the statue to the grotto. However, after two weeks of gazing out the south-facing dining room windows at the magnificent statue standing on the far edge of our ground-level deck, we decided to move the statue just a few feet off the deck from where he was. We had fallen in love with seeing him from the dining nook, which is also where I do much of my writing.

And so I began clearing away the dense grass and brambles and vines and dead fern fronds clogging the ground where we envisioned Ganesha standing in the embrace of two stately ferns, and after a few minutes of work I uncovered a massive flat-topped granite stone butting up against the deck. We briefly considered placing the statue on top of the granite stone, but the top was too narrow and too close to the deck where rambunctious dogs and exuberant children and clumsy adults might unwittingly topple the statue.

When Marcia came outside to see how my work was progressing, I gestured at the mass of dead branches and fern fronds and chunks of old bricks and rotting abalone shells left by the previous owners and said, “The ideal thing would be a little brick pad right in there.”

Marcia nodded, winked at Ganesha, returned to her studio, and as I filled my wheelbarrow again and again with the brittle remnants of the past, I held in my mind’s eye an image of our magnificent Ganesha standing on a small brick pad surrounded by an expanse of gray gravel populated with large stones.

Then something astonishing happened, something a non-believer would call a fortuitous coincidence, and something a devout follower of Ganesha would call His doing.

As I clipped away the last of several dozen dead fern fronds from the lower reaches of a large fern, I espied the corner of a pink brick lying in the ground. Having previously removed several chunks of old brick from the vicinity I thought this might be another such chunk. However, upon removing more of the detritus, I exposed a perfectly level pad made of eight whole bricks.

And that is where our statue stands today, surrounded by an expanse of gravel populated with large granite stones. We have no idea what stood on the brick pad prior to the coming of Ganesha, nor are we certain the brick pad was there before I suggested to Marcia and Ganesha that such a pad should be there. Judging from several other artifacts left behind by the previous owners, I would guess a statue of John Wayne or possibly Ronald Reagan stood where our Ganesha now lords it over the ferns and stones.

I was inspired to write about Ganesha today, remover of obstacles, after a visit to Main Street in Mendocino to view the sturdy white fence recently erected on what is now the end of the sidewalk just to the west of Gallery Books.

A public servant, or as A.A. Milne might have written, a Person Of Very Little Brain, is no doubt behind this blood clot, so to speak, in a major artery of our little town, and as I stood at the ridiculous fence and gazed out over the headlands and Big River Bay, I thought of Monty Python and Mark Twain and the Marx Brothers, for this travesty of a mockery of a sham is a hilarious commentary on how far we humans, collectively speaking, have not come since we climbed down from the trees millions of years ago and sallied forth to people the earth.

Oh Ganesha, Ganapati, Vinakaya—we implore you to help us remove the Dadaesque obstacle on Main Street.