Naomi can count on one hand the number of times she’s left the greater Los Angeles area since she was born in North Hollywood sixty-two years ago. When she was twenty, Naomi married Simon Welch, a real estate agent, and expected to have children soon thereafter. When she didn’t get pregnant after two years of trying, she went to three doctors, each of whom declared her plenty fertile, while Simon refused to see a doctor to determine the viability of his half of the bargain.

Having planned her entire life around having kids, Naomi waited another year and then gave Simon an ultimatum. “Consult a doctor about your potency or I’m filing for divorce.”

Simon steadfastly refused to see a doctor, they divorced, and Naomi went to work as the secretary for a small-time movie producer named Sheldon Reznick. While working for Sheldon, Naomi, who reminded more than a few men of Marilyn Monroe if Marilyn had been short and brunette, caught the eye of a young director named Horace Fielding and he wooed Naomi zealously.

They were married when Naomi was twenty-six and Horace was thirty-three. Naomi got pregnant on their honeymoon in Palm Springs, and when she was eight months pregnant, Horace directed the tiny-budget comedy Your Name Again Was? that eventually grossed over fifty million dollars.

Seven years later, when their son David was seven and their daughter Rachel was five, Horace left Naomi for a nineteen-year-old fashion model from Sweden. By then, Horace had directed seven big-budget movies and he and Naomi were extremely wealthy. In the divorce settlement, Naomi got the five-bedroom house on the beach in Malibu, the condo in Century City, sole custody of the children, and twenty million dollars.

Three years later, when Naomi was thirty-six, she married Myron Lowenstein, a venture capitalist seventeen years her senior, with whom she had her third child, Frieda. Naomi and Myron were married for twenty-six years until Myron’s death three years ago when he was eighty-two.

∆

“What’s so good about Portland?” asks Naomi, talking on the phone to her eighty-seven-year-old mother Golda. “First David moved there, then Frieda, and now Rachel. Finally they’re all about to have children and they want me to move there, too. How can I move? I’ve lived here my whole life. You’re here. I know where everything is. All my friends are here. I offered to buy them houses here, but they had to go to Portland. Why? David can work anywhere on his computer, Rachel can write television shows anywhere, and Frieda could have gone to law school at UCLA or USC. Why Lewis & Clark? Whoever they are. David goes on and on about how beautiful it is there, how fabulous the restaurants. What? We don’t have restaurants here?”

“It rains for hours and hours every day in Portland,” says Golda, angrily. “Those people there get so depressed they kill themselves. In droves. What’s wrong with sunshine?”

“Exactly,” says Naomi, despondently. “Frieda says it doesn’t rain so much there anymore and sometimes they have snow. Since when is snow a good thing?”

“Since never,” says Golda, making a spluttering sound. “Twenty-two winters I lived through in Detroit. If I never see snow again, I’ll be happy. We kissed the ground when we got to Los Angeles.”

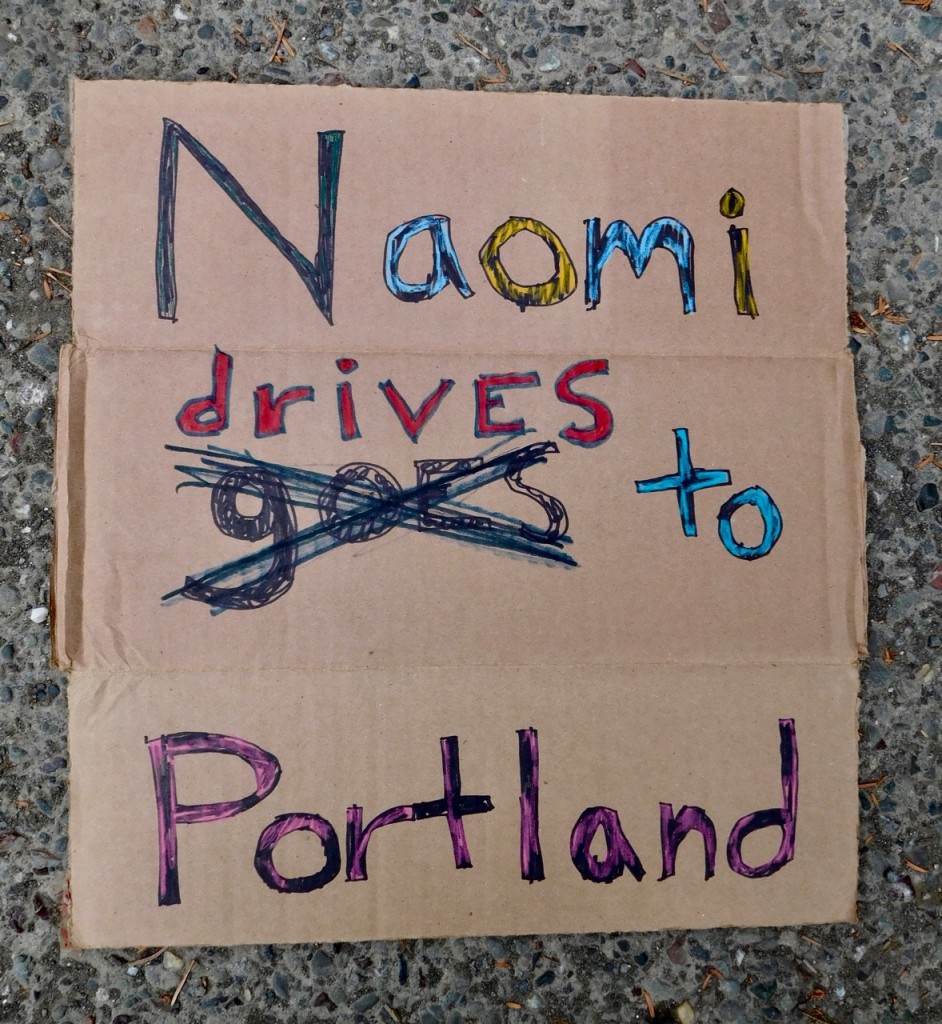

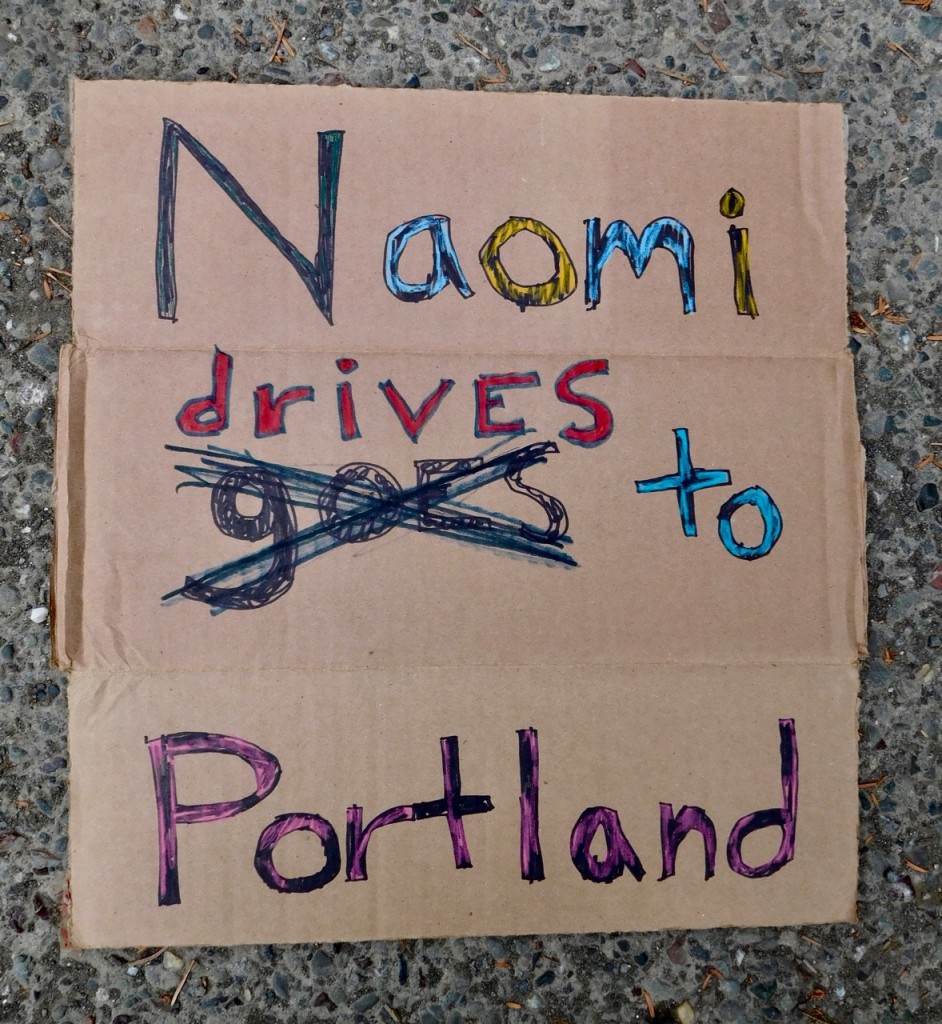

“I’ll kiss the ground when I get back,” says Naomi, starting to cry. “But Rachel is due in three weeks. I have to be with her. I’m driving to Portland day after tomorrow. I’ll be gone for the rest of September and most of October, maybe longer. I’ll call you every day at the usual time. At least they’re in the same time zone.”

“You’re driving?” says Golda, aghast. “That will take forever. Why not fly?”

“I don’t fly, Mama. Remember? I flew to New York that one time with Horace? It was the worst experience of my life. How I lived to tell the tale I’ll never know.”

“His last movie was a bomb,” says Golda, snorting. “Serves him right, the schmuck.”

“Actually that was three movies ago,” says Naomi, who keeps close tabs on Horace’s career. “His last two films have been huge. Horror movies.”

“He should be ashamed.”

“He makes money,” says Naomi, looking around her immaculate home. “That’s all he ever cared about.” She clears her throat. “Money and young women. So I’m leaving Monday. I’ll spend the night with Lisa in San Mateo and then…”

“Lisa? Lisa who?”

“Lisa Leibowitz. You remember Lisa. We went to high school together.”

“I thought she lived in Glendale.”

“She moved to San Mateo twenty years ago.”

“Who knew?”

“I told you hundreds of times.” Naomi rolls her eyes. “Anyway, from San Mateo I drive eight hours to a place called Gold Beach. In Oregon. I’m staying in a motel there that Rachel and David both love. Right on the beach. As if I’m not already right on the beach. And I’ll get to Portland the next day if I don’t get killed first.”

“Why would you get killed?”

“I’m not planning on it,” says Naomi, sighing heavily, “but you never know.”

∆

Naomi makes the drive in her big new silver Mercedes. From Malibu to San Mateo the trip is a piece of cake, and she has a nice visit with Lisa. The traffic she encounters the next morning between San Mateo and Cloverdale reminds her of driving in Los Angeles, but when she gets twenty miles north of Willits on Highway 101, she begins to feel uneasy about the absence of towns and houses; and the disquieting lack of traffic makes her wonder if something terrible has happened in the greater world, something that has made people afraid to go anywhere.

Now quite abruptly the highway shrinks from four lanes to two, with huge trees crowding the road on either side, and she feels she has entered a cold and alien place of endless forests void of people. So to quell her growing panic, she calls her daughter Rachel in Portland, and to her horror, her brand new phone won’t work.

“Why can’t I use my phone?” she asks the onboard computer. “My phone doesn’t work. Why not?”

“No coverage here,” says the robotic voice.

“How far to coverage?” asks Naomi, breathing hard.

“Garberville,” says the voice.

“How far to Garberville?” asks Naomi, her heart pounding.

“Forty-two miles,” says the voice. “At your current speed you will arrive in fifty-seven minutes.”

“Why no coverage until Garberville?” asks Naomi, her voice trembling.

“No coverage until Garberville,” says the voice.

Naomi’s heart is beating so fast, she thinks she might be about to have a heart attack; and just as she has this thought, a pullout appears on her right, so she eases off the road, and there at the far end of the pullout is a young woman holding a baby—a cardboard sign propped up against her backpack saying EUREKA.

And because Naomi is terribly frightened and desperate for help, she pulls up beside the young woman, lowers the passenger window, and says haltingly, “Can you… can you help me? I’m… I’m having trouble breathing.”

“I can help you,” says the young woman, speaking calmly.

“Thank you,” says Naomi, turning off her engine and closing her eyes.

The young woman opens the passenger side door, sets her baby on the passenger seat, hurries around the nose of the car to the driver’s side, opens the door, and places her right hand on Naomi’s shoulder, her left hand on Naomi’s forehead. “You’ll be fine,” she says softly. “Don’t worry. You’ll be fine.”

“Thank you,” says Naomi, keeping her eyes closed. “You’re very kind.”

“Had a scare, huh?” says the young woman, smiling at her baby who smiles back at her. “Where you from?”

“LA,” says Naomi, relaxing a little. “I’ve never been anywhere so far away from anything else, and there were no towns or houses and hardly any traffic, so I started to feel anxious and tried to call my daughter but my phone wouldn’t work, and that threw me into a panic and my heart was racing and I couldn’t get a deep breath and…” She starts to cry. “I thought I was gonna have a heart attack, so…”

“You’ll be fine,” says the young woman, her voice warm and tender. “Everybody gets scared sometimes. You’ll be fine.”

Naomi opens her eyes and smiles at the young woman. “What’s your name? Where are you going?”

“Teresa,” says the young woman, taking her hand away from Naomi’s forehead but keeping her other hand on Naomi’s shoulder. “That’s my boy Jacob. We’re on our way to Portland.”

“Why are you here?” asks Naomi, her panic subsiding. “In the middle of nowhere.”

“I guess so I could help you,” says Teresa, nodding. “I wondered why they dropped us off here instead of in a town. Just out of the blue they pulled over and told me to get out.”

“Who?” asks Naomi, grimacing. “Who would leave you here?”

“It was a couple,” says Teresa, shrugging. “Man and a woman. Picked us up at the north end of Willits. I don’t think she wanted to stop for us, but he did. She wouldn’t talk to me and he wouldn’t stop talking to me and she was not happy about that, so I think she gave him an ultimatum.”

“Are you… are you homeless?” asks Naomi, smiling sadly at Teresa.

“Kind of,” says Teresa, nodding. “At least until we get to Portland. Can you hand me my boy? I think he’s about to throw a fit.”

“Oh don’t do that, Jacob,” says Naomi, talking baby talk to the little boy as she picks him up. “Oh you are such a sweetie pie. Here’s your mother. Don’t worry.”

She hands Jacob to Teresa and gazes at the two of them, and they seem incredibly familiar to her, as if she’s known and loved them forever.

“I know you didn’t stop to give us a ride,” says Teresa, smiling hopefully, “but I sure would appreciate a lift to Garberville. Much better chance of getting a ride from there.”

“Garberville Schmarberville,” says Naomi, beaming at the young mother and child. “I’m taking you to Portland.”

∆

They stop for lunch at a food truck selling Mexican food in the parking lot of a shuttered grocery store on the southern outskirts of Eureka—a dozen pickups parked around the food truck, the clientele mostly laborers, most of them Latinos.

“Is it safe here?” asks Naomi, gazing out her window at the burly men sitting at tables near the food truck.

“Oh, yeah,” says Teresa, nodding assuredly. “And the food is really good. You said you liked Mexican. There’s a fantastic Mexican place in Gold Beach, too, but we won’t get there until dinnertime, so…”

“Maybe I could wait in the car with Jacob,” says Naomi, panicking. “And you get the food.” She rummages in her purse and comes up with a fifty-dollar bill. “How about that?”

“I think I better take him with me,” says Teresa, opening her door. “He’s kind of needy right now.”

“Okay,” says Naomi, taking a deep breath. “I’ll come with you.”

So they get out of the car and the men at the tables and the men in line at the food truck all turn to watch Naomi and Teresa and Jacob approach—Teresa a beautiful young woman with long brown hair dressed in blue jeans and a black sweatshirt, Naomi an attractive woman with perfectly-coiffed short gray hair wearing a long gray skirt and an elegant magenta blouse.

The closer they get to the men, the more terrified Naomi becomes, and she is just about to turn around and run back to her car when a big Mexican man at one of the tables smiles at her and says in English with a thick Spanish accent, “That’s a beautiful car you got there. Es un hybrid, sí?”

“Yes, a hybrid,” says Naomi, laughing nervously. “It’s so quiet you can hardly tell when the engine is running.”

“Es big, too,” says the man, nodding. “I don’t like those little Mercedes, you know? Want that leg room.”

“Yes, leg room is good,” says Naomi, grinning at the man. “You can’t ever have enough leg room.”

The man and his three companions nod in agreement, and Naomi’s fear vanishes.

Teresa hands Jacob to Naomi before stepping up to the window of the food truck to place their order, and as Naomi nuzzles Jacob and makes him chuckle, she is startled to hear Teresa speaking rapid-fire Spanish to the woman in the truck. Until this moment, it never occurred to Naomi that Teresa might be Mexican because Teresa speaks English without an accent and, judging by her appearance, she could easily not be Mexican.

They share a table with three Mexican men and an African American man, the conversation mostly about fishing until the African American man asks Teresa how old Jacob is.

“Ten months,” says Teresa, feeding Jacob a spoonful of rice. “Almost eleven.”

“Big boy,” says the African American man, grinning at Jacob. “Daddy big?”

“Tall,” says Teresa, nodding. “But skinny.”

“You never can tell how big they gonna end up,” says the African American man. “I got three kids and the one who was the littlest baby turned out to be the biggest. He bigger than me, and I’m big.”

“I have three kids, too,” says Naomi, eager to join the conversation. “And come to think of it, David was the smallest of the three and the shortest kid in his class until Fourth Grade, and then he shot up like a weed and ended up six-foot-two. His father was only five-seven. I don’t know how David got so tall. There’s no tall people on either side going way back.”

“My wife,” says one of the Mexican men, “in school, you know, she learn if they get lots of sleep then they grow more.”

“I’m sure that’s true,” says Naomi, liking everyone at the table. “And come to think of it, David was always a great sleeper. He could sleep through anything. I think you’re absolutely right. Sleep is so important. If I don’t get enough sleep, you don’t want be around me. Believe me.”

“I believe you,” says the African American man, nodding. “I don’t get enough sleep, I’m not getting up on a roof.”

“Sí,” says another of the Mexican men. “Remember when Juan came to work so sleepy. That’s when he fell.”

“Got to have sleep,” says the African American man, winking at Naomi. “Sleep is how we charge up those batteries.”

∆

“What a nice bunch of guys we had lunch with,” says Naomi, walking with Teresa and Jacob down an aisle in a Target store in Eureka, a saleswoman wearing a red vest leading the way. “I’m so glad you took us there.”

“I lived here a couple years ago,” says Teresa, nodding. “That was my favorite place to eat. I’m glad you liked it. Thanks for treating us.”

“Here we are,” says the red-vested woman. “These three car seats are all good for infants. You’ll need a bigger one in a couple years when he’s a toddler.”

“Which is the best one?” asks Naomi, gazing at the selection of car seats.

“This one,” says the woman, touching the biggest one. “You don’t want to skimp on your car seat.”

“Never,” says Naomi, shaking her head. “We’ll take that one. Could someone to show us how to hook it up in my car?”

“Um…” says the woman, frowning. “We don’t usually do that sort of thing.”

“I know how they work,” says Teresa, nodding confidently. “Not a problem.”

∆

Jacob fusses a little when he is strapped into the car seat for the first time, so Teresa sits beside him on the backseat, caressing him and singing to him until at last he falls asleep; and the moment his eyes close, Teresa falls asleep, too.

And though Naomi is once again driving through a wild land of endless forests, she is no longer afraid.

∆

Darkness is falling when they get to the Pacific Reef Motel in Gold Beach. Naomi gets a room for Teresa and Jacob adjacent to her room, and while Teresa takes a shower, Naomi plays with Jacob and talks on the phone with her daughter Rachel.

“Everything is going just fine,” says Naomi, sitting on the floor and holding Jacob’s hand as he stands next to her, trying to stay upright. “I had a fabulous lunch in Eureka and I’m looking forward to supper here in Gold Beach.”

“Go to the Schooner Inn,” says Rachel, her words a command not a suggestion. “It’s just right next door to you. It’s the only nice restaurant around there.”

“I may try a little Mexican place a few blocks from here,” says Naomi, laughing as Jacob falls on his butt in slow motion. “I’ve heard it’s terrific.”

“Mom, just go the Schooner Inn,” says Rachel, sounding annoyed. “It’s clean and the food is good. Okay?”

“I’m kind of craving Mexican food,” says Naomi, helping Jacob stand up again.

The little boy gives Naomi an enormous smile and squeals in delight.

“What was that?” asks Rachel, startled by Jacob’s squeal. “Sounded like a baby.”

“There’s a baby next door,” says Naomi, laughing again as Jacob performs another slow motion sit down. “Warm night. The windows are open.”

“Just go to the Schooner, okay? The last thing I want to do is worry about you. Okay?”

“I’m fine, honey. Don’t worry.”

∆

Sated with delicious Mexican food from a little hole in the wall Naomi would never have gone to on her own, Teresa and Naomi and Jacob return to the motel, Teresa changes Jacob’s diaper, nurses him, and he falls fast asleep in the middle of the bed.

Sitting on the floor with their backs against the bed, Naomi and Teresa drink chamomile tea and Teresa says, “So… guess how old I am?”

“Twenty-two,” says Naomi, exhausted and wide-awake at the same time. “Twenty-three?”

“I’m twenty-seven,” says Teresa, shaking her head as if she disbelieves the number. “I had a whole other life until five years ago.”

“Tell me,” says Naomi, nodding encouragingly. “I’d love to hear.”

“I was born in LA,” says Teresa, closing her eyes. “My mother was from New Jersey, my father from Mexico. They met in a restaurant where they both worked. She was the pastry chef and he was a cook. They fell in love, got married, had my brother and me, and we were pretty happy until they got divorced when I was six. My mom got custody of us, but we saw my father on the weekends. He’d take us to the movies or to the beach and we’d get pizza or Mexican food. He was… he was a sweet guy.” She stops talking and sips her tea.

“Where is he now?” asks Naomi, having seen her own father every day of her life until he died ten years ago.

“I don’t know,” says Teresa, wistfully. “We didn’t see him much after I was eleven. He had some other kids with his second wife, but I never got to know them.” She shrugs. “I lost contact with him when we moved to Phoenix when I was sixteen. That’s where I finished high school and went to college at Arizona State.”

“What did you study?” asks Naomi, who never went to college.

“Drama and music.” Teresa makes a self-deprecating face. “I was gonna be a movie star. Silly me.”

“You could be,” says Naomi, knowingly. “You’re beautiful and you move beautifully, and you have a marvelous voice.”

“Thank you,” says Teresa, blushing.

“So then what happened?” asks Naomi, intrigued by Teresa’s story. “After college.”

“I never finished,” says Teresa, shaking her head. “I got really depressed halfway through my junior year.”

“How come?”

“Oh… my mother had this horrible boyfriend who was always hitting on me, you know, and I was afraid to tell her because she really liked him and…” She winces. “You sure you want to hear this?”

“More than anything,” says Naomi, her eyes full of tears.

“Why?” asks Teresa, her heart aching.

“Because I care about you, and because… it’s good to tell our stories to each other.” She touches Teresa’s hand. “That’s what we’re here for. To listen to each other. Don’t you think so?”

“Yeah,” says Teresa, whispering. “Maybe so.”

“No maybe about it,” says Naomi, tapping Teresa’s hand. “So your mother’s boyfriend was hitting on you and you didn’t tell her and…”

“I got into alcohol,” she says, looking away. “And drugs and… then I dropped out and I’ve been on the road ever since.” She looks into Naomi’s eyes. “But I’ve been off all booze and drugs, even pot, since before I got pregnant with Jacob. A little more than two years now.”

“That’s fantastic,” says Naomi, taking hold of Teresa’s hand. “Good for you, Teresa. That takes a very strong will. I’m proud of you. And who is Jacob’s father?”

“He was a graduate student at the University of Washington,” she says, allowing herself to cry. “I thought I’d finally found a really good guy to be with. He said he wanted to marry me, but when I got pregnant he told me to get an abortion, and when I wouldn’t, he wouldn’t see me anymore. So… here I am.” She shrugs. “That’s the short version. I’ll spare you the gritty details.”

“So tell me this,” says Naomi, giving Teresa’s hand a tender squeeze. “If you had plenty of money, what would you do?”

“I’d get a room in a house in a good school district,” she says, nodding assuredly. “For Jacob. And I’d get a job and go to night school and get a degree in Psychology and become a counselor or a therapist.”

“That sounds wonderful,” says Naomi, excitedly. “That sounds like something I should do.”

∆

The next morning, after they take a long walk on a vast wild beach, they have breakfast in a café attached to a bookstore, and when their food arrives, Teresa bursts into tears.

“What’s wrong, dear?” asks Naomi, putting a hand on Teresa’s shoulder.

“I’m just… I’m just so grateful,” she says, weeping. “Last night… that was the first really good night’s sleep I’ve had in a long time, and all this good food… my milk is coming good again for Jacob.” She looks at Naomi. “You’re an angel.”

“You’re the angel,” says Naomi, putting her arms around Teresa. “I’m just a rich person who was afraid of the world until now.”

∆

Inching along the freeway ten miles south of Portland, Naomi turns to Teresa and says, “Where am I taking you?”

“Downtown,” says Teresa, smiling brightly. “Anywhere downtown.”

“You have a place to stay?” asks Naomi, frowning.

“There’s a woman who let me sleep on her porch last year,” says Teresa, nodding. “She was real nice. I’m pretty sure she’ll let me stay there again.”

“No,” says Naomi, shaking her head. “You need a place to live. We’ll get you a motel room, and tomorrow we’ll start looking for a house.”

“A house?” says Teresa, staring at Naomi as if she’s insane. “What are you talking about?”

“You need a place to live and I need a house in Portland,” says Naomi, glaring at the stuck traffic. “What’s going on here? This is just like LA. Is this why my kids moved here? Because it reminds them of home?” She smiles at Teresa. “After all these years they’re finally having children and they want me to move here. And though I’m not ready to move here permanently, I will be spending lots of time here. So… I’ll buy a house and you can live there and take care of the place when I’m not here, and help me with the place when I am here. You can go back to school, and you and Jacob will have a home and I’ll be his grandmother.”

Teresa looks out the window at a homeless encampment next to the freeway and sees a man in filthy clothes crawl out of a battered tent, his face etched with lines of worry.

Now she takes a deep breath and closes her eyes and sees a beautiful old house on a tree-lined street, the sidewalk covered with snow, Naomi coming out the front door wearing a fur hat and a long black coat; and she’s holding the hand of a little boy bundled up in a snowsuit—Jacob three years from now.

“Okay,” says Teresa, opening her eyes and looking at Naomi. “I guess that’s what God wants for us.”

“I don’t know about God,” says Naomi, smiling through her tears, “but I know about me and I know about you and I know about Jacob, and if there were ever three people who were meant to be together, we are those people.”

fin